Table of Contents

Winter is gone at last. It’s good to feel warm, to swim and feed again. Oh, the hunger! The human seem as eager as us. After all, ice fishing for carp is challenging and they are back on the bank for some action. I know better than fall for their pitiful tricks! After all, I’ve seen them all. The little ones gather around me for more of my stories. So where was I? Let’s see: it’s almost the end of the 11th century and Old Europe is entering a new era and a series of changes…

Winter is gone at last. It’s good to feel warm, to swim and feed again. Oh, the hunger! The human seem as eager as us. After all, ice fishing for carp is challenging and they are back on the bank for some action. I know better than fall for their pitiful tricks! After all, I’ve seen them all. The little ones gather around me for more of my stories. So where was I? Let’s see: it’s almost the end of the 11th century and Old Europe is entering a new era and a series of changes…

A changing world

First of all, human population was growing fast and people settled as farmers. They could be tenants or serfs of local knights, priests or monks. They began to master the complexity of water work. Watermills were flourishing everywhere and used for the production of flour or fabric. Except for wealthy humans, the major source of food is bread. Those who are rich enough like monastic communities began to show interest in the irrigation process. New monastic orders like the Cistercians didn’t want to be tempted by the secular world and chose humid zones in the deserted countryside, near a stream or a river, to build their abbey. There was also a lot of deforestation going on. Wood was needed to build houses, tools, dams and natural flooding was part of the everyday life. All of this brought a relative prosperity for the humans of the Old country and a lot of interest in water works.

Christian Church was now holding its ground firmly. Abbeys and monasteries were founded all over the country. The church was always uncomfortable with the idea of eating the meat out of four legged animal during certain periods of the year like Advent and Lent or on Fridays. Monks found the idea repulsive. Eating meat was always associated with lust: the way mammals copulated didn’t help. They thought that us fish, with our spawning once a year, were a better source of food with a better moral value! Go figure. On the 12th century the Church reinforced the strict observance of the St Benedict’s rule: it was mandatory not to eat any meat during the 4 weeks of Advent or the 40 days of Lent, every Friday and Saturday. It was not recommended to eat meat on Wednesday either, meaning that medieval humans couldn’t eat meat for 120 days a year at best (for 180 days at worst!).

The second obligation was that the fish had to be sold alive (if not, it had to be salted, dried or smoked). For people living near the sea on coastal area (especially in England and Italy), it was not a big deal, but for the others (more than 100 miles from the coastal area) they had to stick to bread or eat salted (herring) or dry fish (cod). Fish from the sea were very much appreciated and historians now point to the fact that those fish were already over fished around 1360, especially in the North Sea and Scandia area.

So people began to look more closely for what the rivers could offer. Wealthy people of that time ate mostly salmon, trout, eel, pike, perch, lamprey, chub, bream and sturgeon. Even during those times fish tended to be over fished, specially the migrant ones caught in dams or mills. From the 10th to the 12th century the average size of the sturgeon and perch found in archaeological sites shows a decline for those well represented species. People began to build fish tanks which slowly turned into fish ponds.

The concentration of human in towns, cities, abbeys, convents, which produced a large amount of “nutrient loads” (pee and poop!) in streams and therefore in river systems, helped the algae thrive and those shallow waters made ideal conditions for my ancestors to spread. The weather was very mild between the 12 and the 14th century and before the manifestation known as the Little Ice Age which made those warm bodies of water attractive for my ancestors.

Carp in medieval written sources

Here I come and make my grand entrance: I’m a fecund fish, resistant in cold water, amateur of shallow waters, easily transportable and I can grow to a respectable 4-5 pounds in 3 years. I’m the answer to the very religious medieval human’s prayers!

At first, I made it through the Rhine timidly around the 12th century. Hildegard abbess of Bingen in Germany is the first one to spot my ancestors as present in the Rhine River system and tell about them in her “Liber Subtilatum”, a Natural History and philosophical treatise. Archaeologists found bones of my ancestors in Trondheim Abbey (Sweden) where a few of them were kept in a fish pond. In the Somme River, archeologists have found remains of my ancestors at the end of the 12th century and the beginning of the 13th century in different waste disposals, latrines, castle’s ditch and wells.

Then on the 13th century, my ancestors swam all over Europe, first from France then to Netherland, Germany and Czech Republic. I found mention of carp in Encyclopedia, charts, kitchen-castle-abbeys accounts, archeological sites. One of the most famous encyclopedia is the “Liber de Natura Rerum” (book of the nature of things) by Thomas de Cantipre, a French Dominican monk; in part 7 of his book, “de monstris marinis et de piscibus sive fluvialibus” he wrote about eel, crab, conger, trout, salmon, scorpio (sic) and carp and reported a testimony about us by a famous traveler of this time, Jacques of Vitry. There was a real curiosity about new fish. Albert the Great (German) in his “de animalibus libris” and Vincent of Beauvais (French) in Speculum Naturale made me part of their encyclopedia mostly by copying what Cantipre already wrote: “carp a fish with large scales, the female is colored red and cannot give birth until she takes her own milk in her mouth (don’t ask !), carp is hard to catch, skilled at evade nets, loves weedy waters ; its young prefer warm waters”. Yep that’s me!

Feral carp for sale

Fishing rights were owned by Kings or aristocrats. Today you fish with a license, in medieval times you needed your liege’s permission. In 1258, for example, the French king officer, “Prevost” Etienne Boileau (literally meaning Stephen Drinkwater, sort of mayor for Paris!) wrote the “Book of Paris trades” about all the regulations for the professional guilds in Paris, which inspired the royal officers all over the Kingdom. I read the chapter “the fishermen and fish traders of the Seine River”. In Paris, only men from the Fishermen’s Guild could fish between Notre Dame and the East of Paris; paying 5 sols a year (1 French pound equals 20 sols, 1 sol equals 12 deniers, 4 ponds of bread cost 1 denier at that time) to the king’s tenant. The tenant paid 5 sergeants (who were exempted of taxes!) with part of this money to be sure there were no poachers. The fishermen could use a boat and a net with large mesh so they wouldn’t take undersized fishes (1 pound or less). The 5 sergeants monitored the river closely day and night on boat or on foot, making poachers life more difficult.

All the fishes caught were sold by 20 Parisian traders. They paid 2 French pound for this right! They had to sell my ancestors from the “Rock of Fish” near the Pont au Change. The fishermen went there to weight their catch, gave the best fish to the French king’s cook, and set up the price with those traders. Only feral fish (no fish from ponds!) could be sold in Paris. If somebody was caught disobeying those rules, the fishes were seized by the sergeants, given to the Hotel-Dieu (the biggest Hospital in town; fish were supposed to be good to restore the health of the sick!) or to the Chatelet (to help the prisoners amend their way of life!).

Traders kept us fresh in barrels with holes in it, underwater. Each trader could hire 20 fish criers who would sell carp all over Paris… Criers had to pay 3 pounds a year to have the right of selling fish, and needed to rent a house in Paris. They were paid 1 denier per 1,000 fish sold and they could only sell 6 carts of fish per day (how much fish a cart could hold isn’t clear). They had to scream a lot!

|

|

Fishermen of the King in the Seine River- Paris

|

Criers loved to sell us carp, because unlike barbels, tenches, breams or eels we were not sold by lot, but by unit and according to our size. Usually my 4 pounds ancestors were sold for an average expensive price of 6 deniers… The most beautiful of my ancestors (trophy fish) always finished on the Royal tables. Fishing was strictly forbidden between mid April and mid May (spawning period). Those rules were copied by multiple European cities and slightly modified in 1289, when using nets was forbidden in the River as well as fishing with more than one hook, and 1327 and 1351 with the creation of 6 jurors whose job was to make sure the fish were of good size and quality.

At the end of the 14th century almost all European courts banned the use of widely popular plants like yew powder, nettle, henbane, aconite, alkanet and spurge to stun the fish. It was not only damaging us carp but damaging for the human as well ! All caustic products were also banned. Good sense prevailed !

Carp, a royal and delightful meal

The French King and a lot of German, Dutch, Belgian Emperors, princes, dukes or counts (the European elite) were the ones who had the most chance to eat my feral lineage. Human quickly developed a taste for carp. In 1328 when Philippe VI de Valois got married, his cooks used for one banquet 40,000 eggs, 18,000 chicken, 2,000 geese, 4,000 crayfishes, 289 sheep, 85 veals, 82 beefs, 2,000 carp, 700 pikes, 345 herons, and 300 barrels of wine… In 1381 alone, Philippe VI household will eat 1,587 carp, 140 pikes, 140 tench, 160 eels, 25 breams and 15 perch. The same year the city of Beauvais (France) offered 50 carp and 2 little barrels of wine to the troubadours who stopped to play for the mid-Lent Festivities. Carp was an elite meal till the end of the 14th century.

A semi-domesticated lineage and the emergence of a new economical growth

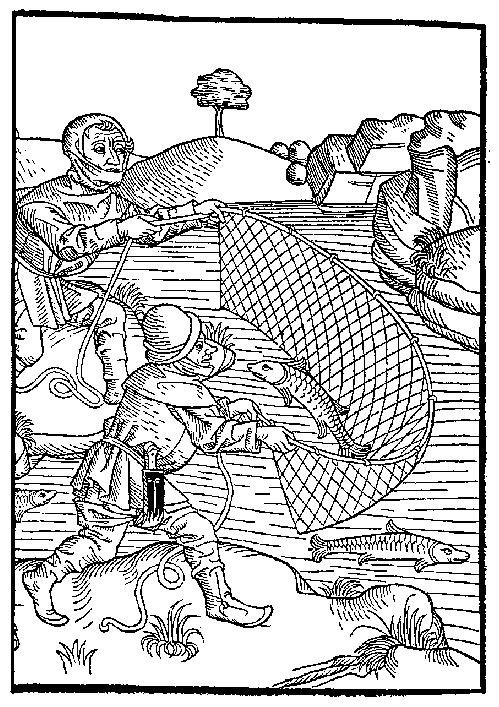

|

|

Men netting fish in a pond (14th century)

|

Kitchen accounts seem to prove that carp began to thrive along the Seine, Rhone and Rhine systems on the 13th century. Carp were fished for consumption only. But fishing was not enough to feed, on a regular basis, people who needed to eat fish according to their religious beliefs. Those who owned the water mills were quick to realize that dams brought fish usually difficult to catch in their waters and gave them the quantity needed to feed their tables. After a while there was surplus they could sell for those who were far from the sea!

The 14th century was a turning point in the development of the fish pond technology. Fish ponds were not only about catching fish and let them breed. Ask the human children who came back home from the fair with a goldfish in their hand. How many of them have lost their fish? Fish ponds were a success in the 14th century because for 400 years human learned a lot about controlling water, let it flow, overflow or runaway.

In 1258, count Thibault of Champagne bought for the large sum of 85 French pounds 3,250 young carp and 6 pikes and for 13 French pounds 10,000 breams, carp and chubs for his fish ponds of the Marne River, a tributary of the Seine. It’s the first mention of the presence of my ancestors in a pond. At the same time Alphonse de Poitiers paid 16,000 French pounds for the Najac castle a huge military fortress with an entire city inside it, do the math! We were not cheap ! The Household of Flemish countess Mahault of Artois kept bread crumbs and food waste to feed the young carp in her fish ponds.

In 1261, the Cistercian Abbey of Heilsbronn (Germany) began to buy all the natural ponds they could put their hands on in their neighborhood. In 1340, those monks possessed a 20 miles long belt of ponds in this part of Franconia where they reared carp and a few pikes for their table and for the citizens of Nuremberg (one of the most active University Center of medieval Germany).

In 1344, a huge fishing session was organized in honor of the Duke of Savoie by the Abbot of Citeaux (Head of the Cistercian Order). The abbey’s menservants caught 27,000 young carp of the year from the Abbey’s fishponds. The biggest fishes were offered to the Duke.

Scriptorium accounts also show that the monks kept the carp bladders. When dried, those were crushed in powder and used as yellow pigments for the manuscript’s illuminations instead of orpiment. A few medicine manuscripts advised monks to use those dried bladders to cure bedwetting for children and elderly… The powder was put in a glass of water and the person would drink that for 8 days and would be cured!

In 1348, Jeanne d’Evreux queen of France, decided it was time to clean 5 of her fish ponds and her castle’s ditch in Nully. The operation was supervised by her steward. He reported that the chief fisherman and 8 helpers fished for 10 days in October and 10 days in February. The ponds produced 2,800 carp and 175 pikes each session.

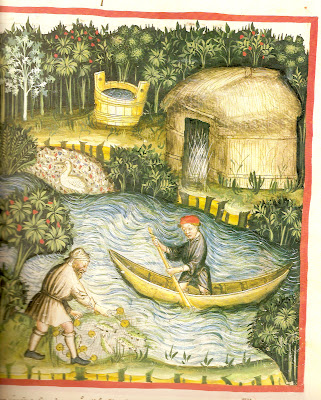

|

|

A nicely designed fish pond (14th century)

|

Emperor Charles IV of the Holy Roman Empire, born in Prague was the one responsible for the creation of ponds in Bohemia. Under his own reign (1347-1378), he supervised the creation of 87 ponds. He was the first to be immortalized fishing for pleasure with a rod in one of his ponds (in a woodcut from the 1515 edition of his autobiography). He was also very proud to remind the reader that he was the inventor of the portable barrel to transport fish alive! The same illustration shows his peasants fishing his pond from a boat with nets.

Prussia was the first country to give their peasants the right to fish for their own household needs as part of their rights in exchange for the mandatory work they would do for their Liege Lord.

The count of Namur in Belgium received around 3,700 carp a year, beginning in 1356 for his tables. Archeologists studied wells of Ename and Woluwe abbeys in Belgium and showed that 90% of the fish bones from the 14th century were carp.

In 1366 the abbot of Citeaux bought 55,862 baby carp. The abbey, rattled by the Black Death and ransacked by the English Army in 1360 and 1365 had to stock new fish in its ponds.

In 1361-62, kitchen accounts of the duke of Burgundy show that he acquired 33,766 carp and 2,739 pikes from the ponds of his castles. 60% of those fish finished on the Pope’s tables, giving back the Duke a solid profit in return. Between 1378 and 1381, monks of Maizieres sold 20,000 young carp to the Duke of Burgundy for 90 French pounds. The duke sold only 10% of these grown fish on the market. Each carp at this time is sold 1 to 5 sols per fish. The profit he made was pretty good (around 160 French pounds for only 10% of the fish sold).

Organization of the fishpond economy in Europe

At the end of the 14th century, a solid branch of my ancestors established themselves as the preferred food of the religious and aristocracy as well as the wealthy merchants, traders and in the big cities of Europe (except in England and Italy where sea food was abundant). The creation of fishponds was a case of “learning by trial and error” method. Sometimes the monks would put too much pike which would eat all young carp or a harsh winter would kill all the fish, when the pond was not deep enough… In Citeaux, the monks aware of those imperfections were the first to build sluice gates in their huge ponds capable of regulating the water flooding and therefore improving the productivity of their ponds. They also began to think about raising young carp independently from older specimen.

At the end of the 14th century, all those different people invented what would be the best method to raise us:

- a spawning pound where breeding carp would be kept in a grassy bottom water

- a nursery pond where they would transfer the baby carp after the spawning

- a growing pond or fattening pond where they would keep the young carp of a year and more and let them mature into 4 pounds specimen ready to eat or sell.

Young carp would be kept for two years, sometimes up to three years and fed with bread crumbs, grass, maggots and natural nutrients from the latrines or the ditch… Around February this pond would be dried up, carp put in large barrels alive and sold to the markets or put in a fishpond near the abbey or castle to be eaten. Those three types of ponds would communicate with a system of canals and gates. The dried fattening pond would be seeded with barley, wheat or any other cereal. It was supposed to be very fertile. After the harvest was done in August, the pond would be cleaned, filled with water and ready to receive a new lot of spawning carp caught the following spring. It will become the spawning pond and so on. Sometimes the dried pond would be turned into a meadow for the cattle to graze. The manure would help the proliferation of weeds when it would be turn back into a spawning pond, the nursery one would become the fattening one and so on. Speak about circle of life! Note that, at this stage, there was no human intervention in my ancestors breeding process. They were fished from rivers, put in ponds and young carp were raised in captivity and eaten or sold without seeing a river again!

Conclusion

What began as simple fish tanks, retainers or fattening ponds became a sophisticated pond system with dams, bond, flux control, with different ponds for baby and young fish as well as for breeding parents. We, carp, are pleased to say that we contributed to develop the Human’s good health, reinforce their religious beliefs, helped them to develop a new line of work, and gave to many a growing source of revenues. Stay tuned for the “golden age of domestication” where natural ponds will become artificial ones with enormous surface like in Czech Republic, real productivity and huge profits making way for the modern aquaculture. Printers will give the world fishing treatises and with it people will begin to fish for pleasure. But that’s another story!

Sources for this paper were articles written by Richard C. Hoffmann, Brian Fagan, Laurent Raynal, Paul Benoit, Jean de Lannoy, Jean Desse and Nathalie-Desse-Berset.

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.